This falls under the category of questions that were too tedious to explore before mass digitization: How did Strindberg and other Modern Breakthrough writers express negation? There are (at least) three different words in Swedish for “not”:

inte

icke

ej

Thinking about these three words, we can imagine a few spectra upon which they fall:

informal <-> formal

spoken <-> written

neutral <-> emphatic

Which is to say, roughly, that inte is the most informal, spoken, and neutral word for “not,” with ej being the most formal, most-often-written, and emphatic form. There are a lot of exceptions to these generalizations, of course, including the use of icke in the sense of “non-“: icke-våld, icke-medborgare (non-violence, non-citizen). And some translations of the Bible tend towards ej, though that is similar in a sense to other languages (English thee/thy/thine as informal, which paradoxically seem antiquated and thus ultra-formal to modern readers).

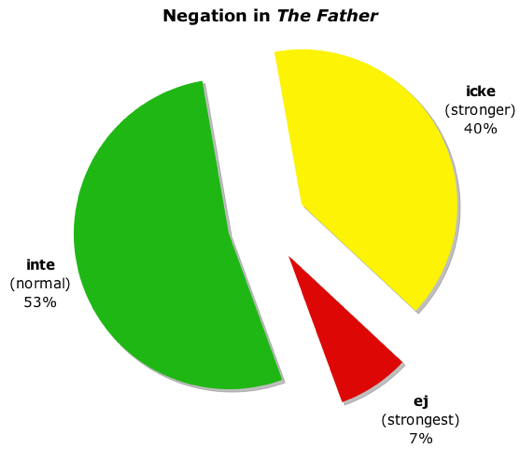

Having said that, what happens when we take a play such as The Father (1887) and do a quick wordcount on the OCR’d text?

So this is not really unexpected, but what we could do to extend this and make it more interesting would be:

1) Changes over the course of the play — more emphatic negation towards the denouement?

2) Gendered negation — do women use more cautious language? (This requires coding each speaker as M/F, which is somewhat easier in a play than a novel due to the way the pages are laid out, but still labor-intensive.)

3) Changes over a long authorship — did early, national-romantic Ibsen use more flowery negation, while later realistic Ibsen use more terms associated with the spoken tongue?

4) When does the use of icke and ej really begin to disappear from the written record? Do these more formal terms hand on longer in scientific material than they do in literature? The linguists working with the Swedish Academy have, of course, their own databases of newspaper and literary material — how far back do those go, and do they match up with what is in Google Books?